|

Roger M McCoy

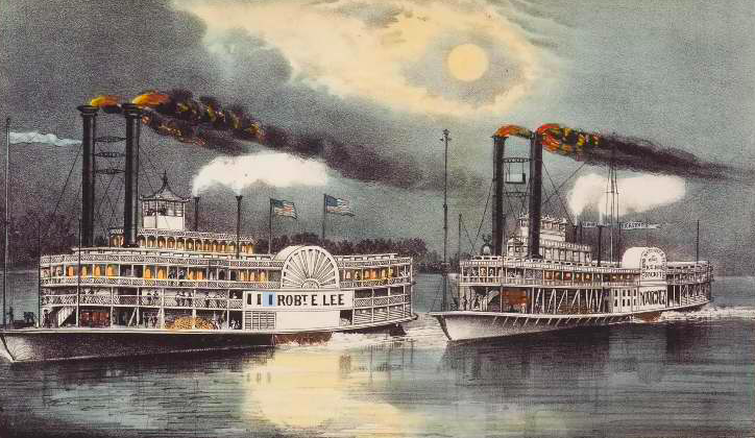

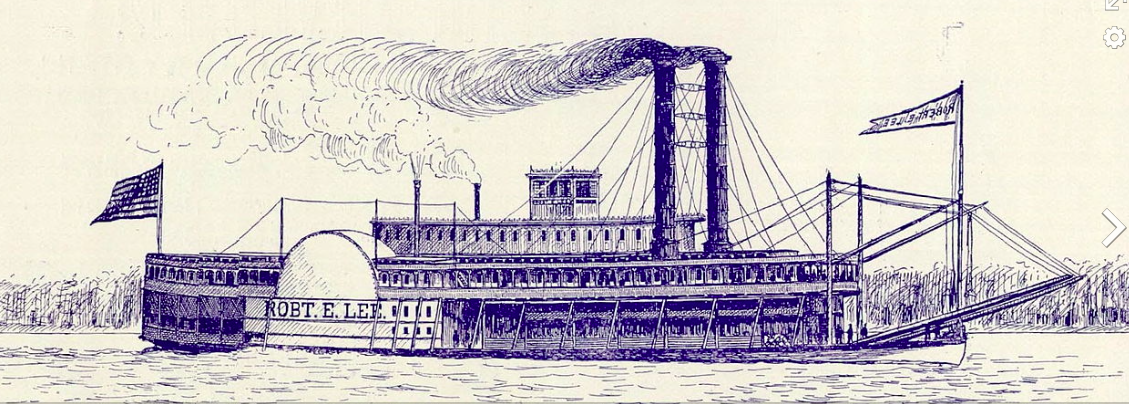

Even in the best conditions riverboats of the nineteenth century faced the hazards of snags, groundings and explosions. As if these hazards were not enough, steamboats soon competed in high risk racing. Racing these boats became popular along with horse racing and dog racing. The public became avid about boat racing, and the crews took great pride in helping their boat win a highly publicized race. In many cases, the races were planned in advance, with spectators lining the riverbanks to enjoy the excitement of the race. Others were impromptu events urged on by passengers looking for a little excitement. Steamboat captains competed as a matter of pride and ego and boat owners believed that a record of wins would draw more passengers. Betting on races was widespread with one highly publicized race drawing more the $1,000,000 in wagers (approximately $30,000,000 today). Mark Twain commented on the excitement of steamboat racing in his usual vivid style: “Two red-hot steamboats raging along, neck-and-neck, straining every nerve—that is to say, every rivet in the boilers—quaking and shaking and groaning from stem to stern, spouting white steam from the pipes, pouring black smoke from the chimneys, raining down sparks, parting the river into long breaks of hissing foam—this is sport that makes a body’s very liver curl with enjoyment.” The phrase “straining…every rivet in the boilers…” should be enough to convince anyone that steamboat racing was risky. One steamboat race became a major event with thousands of spectators. It was a race between the Robert E. Lee and the Natchez steaming from New Orleans to St. Louis. The history of the Natchez steamboat shows nine riverboats by that name, the first built in 1823. Fire destroyed the sixth Natchez in 1863. The ninth Natchez, built in 1957, still operates as a tourist attraction in New Orleans. The seventh Natchez famous for racing the Robert E. Lee was built in 1869 in Cincinnati, Ohio. She was 301 feet long, had eight boilers and a capacity of 5,500 cotton bales. In her nearly ten years of service, she made 401 trips with no serious accidents. This Natchez had beaten the previous steamboat speed record in 1844 and was a good match for the famous race. The Robert E. Lee was built in the Ohio River town of New Albany, Indiana, in 1866. As it happens there had been two previous steamboats named Robert E. Lee. This stately boat was nicknamed the “Monarch of the Mississippi.” So how did this much-publicized race proceed? It began in New Orleans on June 30th, 1870, with the Robert E. Lee pulling ahead from the beginning and gaining a lead of several hours in the first day. Then both boats began to experience equipment problems. The Robert E. Lee burst a steam pipe the first night allowing the Natchez to come within three minutes of her, the closest margin of the race. Later the Natchez lost a water pump that cost it thirty minutes. Then it had to stop because of fog for five hours. In the end the Robert E. Lee arrived in St. Louis on July 4, 1870 around 11:30 am in the morning; the Natchez followed, arriving at 6:00 pm. Crowds of people in East St. Louis and St. Louis came to the river banks to watch the arrivals. This famous race had several elements that made it a competition between two boats traveling under very different conditions. Although both boats were comparable in size and power, their captains had different approaches to the race. On board the Robert E. Lee were only seventy-five specially invited guests and no cargo. Captain John W. Cannon outfitted the Lee to race. The Natchez under the command of Captain Thomas Paul Leathers, prepared for a regular trip, taking on board a full complement of passengers and cargo. The Natchez made regular stops for fuel and to unload cargo. Captain Cannon, on the other hand, made arrangements to refuel the Robert E. Lee while underway. Thus the Robert E. Lee proceeded while carrying no cargo, steaming ahead through fog and made only one stop, and won the race in 3 days, 18 hours and 14 minutes. By contrast, the Natchez carried her normal load and stopped as normal, tying up overnight when fog was encountered. Despite this she finished the race only six hours later than the Robert E. Lee. The race of the Robert E. Lee and the Natchez from New Orleans to St. Louis became immortalized by the prominent lithographers, Currier and Ives, and their well-known print forms the masthead for this series of blogs on nineteenth-century riverboats. Several other paintings of the great race have been made but the Currier and Ives picture is the best known. Such racing involved major risks. Steamboat racing became highly popular and sometimes deadly. In some cases the races were planned and advertised in advance, with spectators lining the riverbanks beforehand to enjoy the spectacle. Others were impromptu affairs, sometimes urged on by the passengers and steamboat captains. Useful as steamboats were, they came with one big problem: they were inherently dangerous. The steam boilers were prone to exploding and igniting fires. The boats were wooden and much of their cargo was highly flammable cotton bales, along with barrels of turpentine and gunpowder. These hazards came in addition to the snags and submerged bars that could rip a hull open. Between 1816 and 1848, boiler explosions alone killed more than 1,800 passengers and crew and injured another 1,000, and racing added significantly to the chance for an explosion. In 1965 noted historian and prolific writer Daniel Boorstin commented, “A voyage on the Mississippi was far more dangerous than a passage across the ocean.” A nineteenth-century humorist, Charles Godfrey Leland, said much the same about steamboat racing. “From the days of the Romans and Norsemen down to the present time, there was never any form of amusement discovered so daring, so dangerous, and so exciting as a steamboat race,” Such racing is, of course, inevitable given the human inclination to compete, to demonstrate their skill, and show the superiority of their boat. Sources: Discover Indiana. https://publichistory.iupui.edu/items/show/146 Springfield Museum. Springfield, Massachusetts The Great Mississippi Steamboat Race From New Orleans to St. Louis, July 1870, Currier & Ives. https://springfieldmuseums.org/collections/item/the-great-mississippi-steamboat-race-from-new-orleans-to-st-louis-july-1870-currier-ives/ Thomas, Christian. For Profit and Glory: Steamboat racing on the inland rivers. https://www.howardsteamboatmuseum.org/river-history/for-profit-glory-steamboat-racing-inland-rivers/ Twain, Mark. 1885. Life on the Mississippi. retrieved from: Gutenberg Books, https://www.museum.state.il.us /RiverWeb/landings/Ambot/SOCIETY/SOC8.htm https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_E._Lee_(steamboat) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Natchez_(boat) https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-deadly-steamboat-races-enthralled-america-180982038/

1 Comment

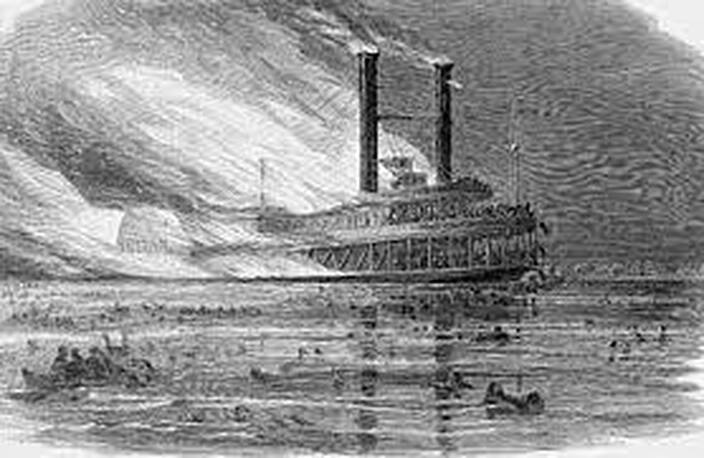

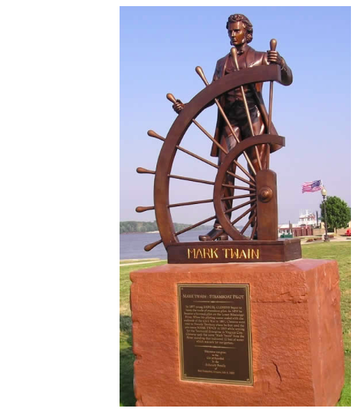

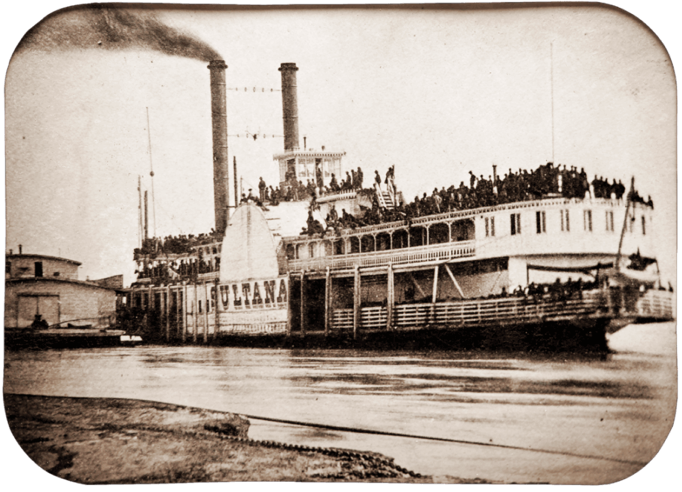

The Sultana in flames following explosion. Note the people floating in the river. Contemporary drawing. Artist unknown. The Sultana in flames following explosion. Note the people floating in the river. Contemporary drawing. Artist unknown. In the early nineteenth century steam-powered riverboats were the major form of transportation for people and cargos in three immense river basins in the young United States: the Mississippi River, the Ohio River, and the Missouri River. Also canals connected cities like New York and Chicago to the great river network of mid-America until railroads provided better and faster service in the mid-nineteenth century. The size of many nineteenth-century riverboats was a problem in itself. Some steamers were so long, over 200 feet, that they undulated with the waves as they traveled despite beams and braces to help keep the boat rigid. A passenger noted that you could see the wave coming down the length of the boat. The riverboats were not without risk and they often met with disaster by hitting submerged objects such as fallen trees or sandbars. Either of these hazards could break open the hull, although the sandbar in some cases only grounded the boat temporarily. The disaster most feared by the traveling public aboard a nineteenth- century riverboat was boiler explosions. The explosion of the riverboat Sultana on the Mississippi River had such a high death toll that public pressure forced Congress to enact the nation’s first transportation safety act. Author Charles Dickens visited America in 1842 and traveled by riverboat on the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to Cincinnati. As he learned more about the boats he observed, “…steamboats usually blow up one or two a week in the season.” Such knowledge, however, did not deter the number of people traveling on riverboats, or reduce cargo shipments. Boat builders valued the importance of good weight distribution. To achieve this they put the boilers near the front—the bow—and the machinery in the middle or at the stern. They attempted to stiffen the long framework of the hull with trusses and long iron rods. Unfortunately putting the boilers near the bow paved the way for death and destruction for thousands of passengers whose cabins were located on the deck above the boilers. Passengers lives were never in greater jeopardy than when they stood on the upper decks while watching workers loading cargo at a landing. Many explosions occurred at landings due to the increase of pressure when the engines were stopped. The first recorded explosion on a Mississippi River steamer was in 1816. The steam pipe on the Washington burst and nine men were scalded to death. In the following year the Constitution blew up, and thirty lives were lost. Over time a frightful toll of boats and lives occurred on steamboats. Congress began moving to regulate steamboat boilers. In 1849 a list of 233 explosions on river steamers was compiled for the purpose of informing Congress on the question of steamboat boilers. The list showed that, as nearly as could be ascertained, 2,563 lives were lost and 2,007 persons injured in the explosions, a total of 4,660. The property loss was placed at $3,090,360 (1.2 billion today). One important riverboat, the Sultana, set records when it exploded on the Mississippi River in 1865, only a few weeks after the end of the Civil War. At the time of the explosion the Sultana was carrying an estimated 2000 Union soldiers who had been held in Confederate prisoner of war camps (for comparison, the Titanic disaster took 1503 lives). Many of the returning soldiers came from Confederate hospitals or prisons in poor condition and disabled. The Sultana was docked in Vicksburg for boiler repairs when it’s Captain, Cass Mason, heard that the U.S. government would pay an attractive sum to transport soldiers ($90 each). He decided a thorough repair of the boiler would cause him to miss this opportunity, so he ordered a quick and temporary fix. In order to take maximum advantage of the government offer, Captain Mason also accepted many more soldiers than the Sultana was designed to carry. While underway one of the Sultana’s boilers exploded a few miles north of Memphis, Tennessee at approximately 2 a.m. on April 27, 1865. SOME DEVICES LEAVE A BIG GAP HERE. PLEASE SCROLL DOWN. The explosion instantly killed hundreds, especially those soldiers who had been packed in right against the boilers. Many of them died from shrapnel, steam, and boiling water released from the explosion. Those on deck either went down with the boat of jumped into the river. Those who were able grasped a scrap of a board to stay afloat, and those who knew how to swim might make it to shore or stay afloat for a few hours until the rescue boat arrived. Unfortunately there were few survivors. Among the survivors was a young soldier from Michigan named Hosea Aldrich who described the chaos and confusion after the explosion, “…the first thing that I heard was a terrible crash, everything seemed to be falling. The things I had under my head, my shoes, and some other articles and specimens that I had gathered up and had them tied up in an old pair of drawers, they all went down through the floor. We scrambled back. The smoke came rushing up through the passage made by the exit of the exploded boiler. I was pushed in the water and started for the bottom of the Mississippi, but I soon rose to the surface and found a small piece of board, and soon had the luck of getting a larger board, which was very lucky for me, as I could not swim. We floated along down the river nearly an hour I think when my limbs began to cramp; that was the last of which I was conscious until at eight o'clock a.m. We had floated down the river six miles and lodged in the flood-wood against an island which was within two miles of Memphis, and here we were picked up by the United States picket boat.” Another writer named Jerry Potter wrote: “It was a particularly bad day to be out on the water. The Mississippi River was experiencing high water levels as melting snow from up north flooded its banks. Fallen trees and other debris mixed into the fast-moving waterways. It was difficult to navigate these clogged and swirling waters come nightfall, but Captain Mason was determined to make his shipment of soldiers. Several miles from Memphis, Tennessee, one of the Sultana’s boilers exploded. Because the boat had been so packed, many of the passengers were crammed right by the boilers. The explosion instantly killed hundreds, mostly soldiers from Kentucky and Tennessee who had been packed in right against the boilers. Many of them instantly died from shrapnel, steam, and the boiling water released from the explosion. One minute they were sleeping and the next they found themselves struggling to swim in the very cold Mississippi River. Some passengers burned on the boat. The fortunate ones clung to debris in the river, or to horses and mules that had escaped the boat, hoping to make it to shore, which they could not see because it was dark and the flooded river was at that point almost five miles wide.” All these passengers aboard the Sultana were torn between two choices: stay on the boat and die from the fire or jump into the water and possibly drown. Soldiers just out of war again found themselves fighting for their lives. Fortunately passing boats and local residents began a rescue operation to save the soldiers. One local man, John Fogelman and his sons made a raft from some logs and went to the flaming Sultana to rescue passengers. They made several rescue trips back to the burning boat. One soldier from Ohio noted, “When I came to my senses I found myself surrounded by wreckage, and in the midst of smoke and fire. The agonizing shrieks and groans of the injured and dying were heart-rending, and the stench of burning flesh was intolerable and beyond my power of description.” Within a few hours the Sultana went to the bottom of the Mississippi. One curious feature of this disaster is that some of the rescuers, who were defeated Confederate soldiers only a few weeks earlier, now saved the lives of their former enemy. The cause of the Sultana explosion can be laid on Captain Mason. His neglect of equipment and refusal to make adequate repairs plus his eagerness to make a bundle of money cost many lives. Sources: Young, David. Roiling on the River. Chicago Tribune 2003. Retrieved from: https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-2003-01-12-0301120511-story.html Berry, Chester D. Loss of the Sultana and Reminiscences of Survivors. Lansing, Michigan: Darius D. Thorp, Printer and Binder. 1892. Comstock, Daniel W. Ninth Cavalry: One Hundredth and Twenty-first Regiment Volunteers. Richmond, Indiana: J.M. Coe Publisher. 1890. Retrieved from https://www.gutenberg.org/files/60363/60363-h/60363-h.htm Larry Holzwarth. See 1842 America Through Charles Dickens’ Eyes. Retrieved from: https://historycollection.com/see-1842-america-through-charles-dickens-eyes/13/ Aldrich, Hosea C. and Hatch, Absalom N. Returning Prisoners of War. Michigan Family History Network. Retrieved from: http://www. mifamilyhistory.org/civilwar/sultana. 1865.  Monument to Mark Twain on riverfront of Hannibal, Missouri. Monument to Mark Twain on riverfront of Hannibal, Missouri. Roger McCoy Many boys in the nineteenth century watched riverboats coming and going and held the dream of becoming a boat pilot. Just as today a child might dream of becoming a railroad engineer or an airplane pilot, young boys then wanted the glamorous and prestigious job of steering a riverboat. The only way to achieve this dream was to start as a cub (apprentice) in one of the other jobs and eventually become a cub pilot. This usually required convincing a current boat pilot to take on teaching a young man to handle the boat. The best known account of learning to be a riverboat pilot comes from Samuel Clemens who worked on a riverboat and eventually convinced the boat’s pilot to take him on as a cub pilot. His original intention was to travel down the river to New Orleans and find a ship headed to the Amazon River. He soon discovered that no ship was likely to head for the Amazon for ten or twelve years and that his remaining ten dollars was insufficient for his plan. Clemens resolved to give up the idea of becoming an Amazon explorer and “contrive a new career.” He later wrote, “When I was a boy, there was but one permanent ambition among my comrades in our village on the west bank of the Mississippi River. That was, to be a steamboatman.” !n 1857 the twenty-one year-old Clemens was traveling on the steamboat Paul Jones and he worked up an acquaintance with the pilot. “I planned a siege against my pilot, and at the end of three hard days he surrendered. He agreed to teach me the MIssissippi River from New Orleans to St. Louis for five hundred dollars [equivalent to $19,000+ today], payable out of the wages I should receive after graduating. I entered upon the enterprise of learning twelve or thirteen hundred miles of the great Mississippi River with the easy confidence of my time of life. I supposed that all a pilot had to do was to keep his boat in the river, and I did not consider that could be much of a trick, since it was so wide.” After four hours into his first voyage Clemens’ chief suddenly said, “Here you take her; shave those steamships as close as you’d peel an apple.” The young Clemens’ heart “fluttered up into the hundreds for it seemed we were about to scrape the side off every ship on the line we were so close.” After a few tense minutes of seeming peril, the chief pilot “flayed me alive for my cowardice” because Clemens had been overly cautious near the other boats. Clemens admitted his admiration for the ease the pilot showed in handling the boat, and after the pilot’s temper cooled a bit he resumed his instruction of the young cub. The pilot told Clemens, “the easy water was close ashore and the current outside, and therefore we must hug the bank, up-stream and stay well out, down-stream.” At that point Clemens resolved that he would be a down-stream pilot and leave the up-streaming to people with no concern for risk. At the end of his first watch the young Clemens ate supper and went to bed. At midnight his next watch began with the night watchman shining a lantern in Clemens’ eyes with the harsh words, “Come! Turn out!” Clemens dozed off to sleep as soon as the watchman left. The man with the lantern soon returned and was by now distinctly annoyed at Clemens’ disobedience. Clemens was further embarrassed by jeers of the previous watch just turning in. “Hey watchman! ain't the new cub turned out yet? He's delicate, likely. Give him some sugar in a rag and send for the chambermaid to sing rock-a-by-baby to him.” [NOTE: In the nineteenth century fussy babies were given a bit of sugar tied into the corner of a rag giving rise to the term “sugar tit.”] Clemens reluctantly realized that a pilot needing to get up in the middle of the night was a detail of the job that had never occurred to him. He knew that boats ran all night but had never realized “that somebody had to get up out of a warm bed to run them.” On his midnight watch Mr Bixby, the pilot began to question Clemens about the names of shoreline features and Clemens had no answers. As it turned out this was the information Bixby had been telling the previous day to teach him the river. Finally the exasperated Bixby said in an unusually calm manner, “My boy, you must get a little memorandum book, and every time I tell you a thing, put it down right away. There's only one way to be a pilot, and that is to get this entire river by heart. You have to know it just like ABC.” Clemens wrote that he soon realized, I have not only to get the names of all the towns and islands and bends, and so on, by heart, but I must even get up a warm personal acquaintanceship with every old snag and one-limbed cotton-wood and obscure wood pile that ornaments the banks of this river for twelve hundred miles; and more than that, I must actually know where these things are in the dark. This indeed was the crux of being a pilot on a Mississippi River boat. Another nineteenth century pilot and writer, George Merrick, confirmed Clemens’ observation with the comment: To know the river under those conditions meant to know absolutely the outline of every range of bluffs and hills, as well as every isolated knob or even tree-top. It meant that the man at the wheel must know these outlines absolutely, under the constantly changing point of view of the moving steamer; so that he might confidently point his steamer at a solid wall of blackness, and guided only by the shapes of distant hills, and by the mental picture which he had of them, know the exact moment at which to put his wheel over and sheer his boat away from an impending bank. Clemens’ chief pilot, Bixby, was later assigned to a different, bigger and more luxurious boat and Clemens went with him. He was beginning to understand the complexities of being a riverboat pilot. After two years as apprentice the young man named Samuel Clemens received his steamboat pilot’s license. Then he began piloting boats on his own for two years, until the Civil War halted steamboat traffic. During his time as a pilot, he picked up the term “Mark Twain,” a boatman’s call noting that the river was only two fathoms deep, the minimum depth for safe navigation. When Clemens returned to writing in 1861, working for the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, he wrote a humorous travel letter signed by “Mark Twain” and continued to use the pseudonym for nearly 50 years. Sources: https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/mark-Clemens-receives-steamboat-pilots-license http://www.twainquotes.com/Steamboats/Introduction.html Clemens, Samuel L. 1885. Life on the Mississippi. retrieved from: Gutenberg Books, <https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/245/pg245-images.html#linkc6> Merrick, G. B. 1909. Old Times on the Upper Mississippi: Recollections of Steamboat Pilot from 1854 to 1863. Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company: Ohio. Roger McCoy

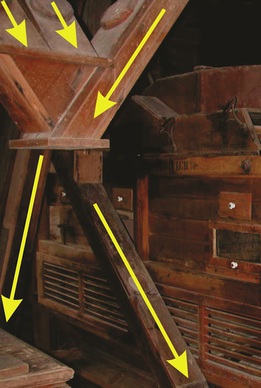

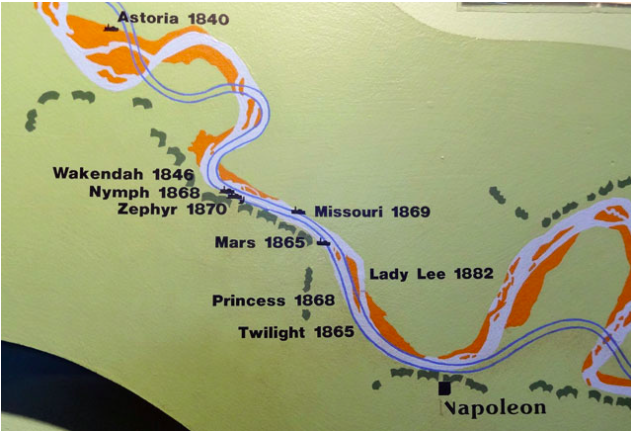

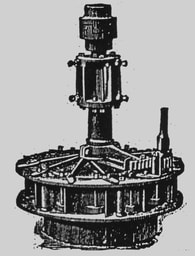

(Hover to see captions. Click/tap to enlarge.) The typical riverboat of the nineteenth century had a short life filled with many hazards, and an average life expectancy of only two to five years. The most common hazards were boiler explosions and under-water obstructions such as fallen trees (snags). One thoroughly documented case of the latter was the elegant riverboat, Arabia. The riverboat Arabia began its life in 1853 at a boatyard operated by John Pringle in Pennsylvania. This 171 foot-long riverboat with two side paddles traveled down the Ohio River to St Louis where it began service on the Missouri River. Each river has its hazards, but the Missouri River was known and feared among riverboat pilots for its many snags and submerged bars. On September 5, 1856 this ill-fated riverboat struck a submerged tree and vanished beneath the muddy waters of the Missouri River. Fortunately the 150 passengers and crew made it off the boat safely, but the boat went down and 200 tons of cargo were lost to the muddy river and slowly became buried in the silt. Over the years the river channel meandered and shifted to new positions and left the Arabia buried for more than 130 years. In 1987 a treasure hunter, David Hawley, researched the disaster and decided the steamboat Arabia then lay buried somewhere below a Kansas cornfield west of Kansas City. He was inspired by the possibility of gold and other valuables on the sunken boat. In the winter of 1988 David Hawley, along with his father Bob and brother Greg, decided to excavate to recover any valuables. Years of erosion and shifting channels left the sunken paddleboat 45 feet underground and a half-mile away from the present channel of the Missouri River. The three Hawleys partnered with long-time friend and customer Jerry Mackey, who operated a local fast food chain. Shortly after, the fifth and final member of the team, construction business owner David Luttrell, joined the team—and, together, these five men set out to recover the Arabia’s long lost cargo. As David Hawley pushed through the corn stalks with his metal detector he estimated he was near the middle of what once had been the river's channel. Hawley said he could hardly see where he was going among the tall corn stalks, but he walked back and forth through the field for most of the afternoon when suddenly the chirping of the magnetometer accelerated and he knew he had found the Arabia. Hawley said he suddenly felt excited “like a kid in a candy store.” Hawley, his father and brother had spent years searching for some of the nearly 300 documented sunken Missouri River steamboats hoping to find valuable cargoes of gold or whiskey. They had little to show for their efforts except old, rotted boat timbers and one load of soggy salt pork. But on that afternoon in 1987 they hit a bonanza. After years of searching for wrecks as treasure hunters, the discovery of the Arabia transformed them into archaeologists, fundraisers, and museum builders. During his early research, Hawley found that Arabia had been launched in 1853 on the Monongahela River in Pennsylvania. A newspaper of the time described the boat as a "handsome and staunch packet...furnished throughout with the latest accommodations and improvements for the comforts of the passengers and conveyance of freight.” The Hawleys had also found an 1856 newspaper with an eyewitness account of Arabia's last moments: "There was a wild scene on board," recalled a survivor named Abel Kirk. "The boat went down till the water came over the deck, and the boat keeled over on one side. The chairs and stools were tumbled about and many of the children nearly fell into the water." Amazingly, considering that Arabia sank in less than ten minutes, all 130 passengers and crew survived. The one fatality was a mule tied on deck as the boat sank. Another passenger, J.H. Garside recalled, "We had quite a memorable history in ascending the Missouri River in reaching our destination. The boat Arabia sank just above Kansas City about 6 miles, near Parkville, Missouri at dusk and we were all required to take life boats to reach the Missouri shore and camped there all night until parties from Parkville came down to take us to their town. We stayed there for about 30 days before we could catch a through boat to Nebraska City.” The Parkville newspaper printed an account of the wreck the following day: “On last Friday evening just before nightfall the Missouri River passenger steamer while nearing our city struck a snag which perforated the hull in so serious a manner that she sunk in the short space of ten minutes in twelve feet of water. No lives were lost but the boat and her cargo, which was very large, is a total loss. …We do not know whether the insurance companies will attempt to recover the cargo or not. It would seem to be a hopeless task as the water is now running over her hurricane deck in one or two places where the vessel broke in two. (NOTE: The hurricane deck was the uppermost deck on the boat. The pilot house was often on the hurricane deck.) Hawley’s partner, David Luttrell, owned a construction company and brought bulldozers and a large excavator. The five men were now ready to begin digging in the summer of 1987, but the farmer insisted they wait until the corn was harvested in late September. Finally they began digging in mid-November, working many 12 and 14-hour days, seven days a week. On dry days, sand worked its way into their ears, noses and mouths. During wet weather, the water table rose and they fought mudslides and floods that surged unpredictably out of the spongy, soggy soil. To remove water from the site faster than it seeped in, they installed a system of pumps, each pumping 1,000 gallons per minute. The pumps had to be dismantled to prevent them from freezing at night, then laboriously reassembled the next morning. Bulldozers cut into what had once been the Missouri's channel until they were nearly 30 feet below ground level. On November 30, after 17 days of excavation, one digging machine scraped across a piece of wood. It proved to be Arabia's left paddle wheel. A few days later, the top of a barrel appeared in the ooze. When they pried off the barrel's lid, Hawley reached into the mud and discovered an assortment of fine cups and dishes—exquisite Wedgwood china. Soon the digging crew uncovered thousands of objects in barrels including china, clothing tools and innumerable other items. Aware that exposure to oxygen would quickly destroy fabric and metal alike, the Hawleys stored many items in commercial freezers. Also they rented huge water tanks to store wooden artifacts, including timbers, that needed to be kept in water to prevent shrinking and cracking. In short, everything they found, wood, metal, or fabric needed care to prevent rapid deterioration from exposure to air. In 1991, the Arabia’s cargo was transformed into the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City, Missouri. From fine china and carpentry tools to children’s toys and jars of the world’s oldest pickles, the museum holds an impressive display of Arabia’s artifacts retrieved from the Missouri River, “the river that eats boats.” The collection is a work in progress as preservationists continue to clean tons of artifacts in a preservation lab. The museum of the steamboat Arabia shows a fascinating slice of life in 1850s America.  Photograph of spouts that move grain or flour to lower levels. Photograph of spouts that move grain or flour to lower levels. Lise Schools, Interpretive Planner, Indiana State Parks In the 1790s the American frontier began to push westward from the thirteen original colonies. The edge of the western frontier moved like a game of leapfrog. Settlers would claim the forested land and begin the arduous task of clearing it for crops. As those farms became established, the next wave of settlers would pass the first, moving the frontier border further west. Many of these first settlers in Ohio and Indiana territories were Revolutionary War veterans whom the new government paid in land in this cash-poor, but land-rich new country. As farmers cleared additional acreage in subsequent years, individual farms transitioned from subsistence to surplus. The need arose for mills to grind surplus grain, and for the means to transport finished flour from the frontier to markets in the east and south. Some farms had access to small hand-cranked mills. Horse-powered mills required a farmer to harness his horse to a horizontal pole attached to grindstones in the center of a circle. The horse walked in circles, turning the upper grindstone against the stationary lower stone, converting corn to cornmeal. The most common style of mill was water-powered created (see picture above) by damming a creek and creating a mill pond. The mill structure, located at the dam, would guide water from the pond through a narrow chute, turning a vertical wheel. A shaft attached to the wheel turned the grindstones. It was a technology that dated to 4000 B.C.E. or earlier. Water routes were the main highways for transporting grain, finished flour, and other commodities out of the frontier. Short-lived canal systems connected the midwest to the east coast. The financial and engineering challenges faced by canals led to their early demise. An alternative was to load barrels of flour, grain, and pork onto flatboats which were floated down creeks to larger tributaries. Once the flatboats reached the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, items could be shipped on steamboats to New Orleans, or continue the journey on flatboats (see picture above). The surplus of grain grew until farmers arriving at a mill with their grain would sometimes need to wait in line for days. Communities soon formed around early mills with an inn and tavern to provide sleeping accommodations, food, and beverage for the waiting farmers. Once their grain was ground and exchanged, farmers had cash. The general store sold needed goods from the east such as hardware and fabric. A blacksmith for shoeing horses, and a post office were other early businesses that surrounded a mill. One item in short supply at the edge of the frontier was labor. Milling was still a “bag and shoulder” process, unchanged from the 1500s, and requiring many strong backs. Up until this time, mill construction and operation were closely guarded secrets. In 1795, during the Industrial Revolution, inventor Oliver Evans (1755-1819) published his trade manual, The Young Mill-Wright’s and Miller’s Guide. This book set some standards of operation for mills. Evans writes, “He that studies and writes on improvements of the arts and sciences labors to the benefit of generations yet unborn …” Oliver Evans made the milling process more accessible to entrepreneurs. More importantly, Evans’s manual included a mechanized mill design that produced more flour, using half the labor of a traditional mill. While water still powered the mill’s grindstones, it also powered many other parts of the mill. Elevators, a continuous strap with attached buckets, lifted the grain from the ground floor to the top of the mill. Spouts sent the grain from the top floor to various processes or storage bins. Conveyors, using the principle of the Archimedes screw, moved flour horizontally through the mill. In addition to the mechanization, other adaptations were incorporated into mill design to increase productivity. For example: Height: Mills were several stories high to assist operations that relied on gravity. Windows: Due to extreme fire hazard from flour dust, lanterns, lamps, and torches were prohibited. Numerous tall windows brought natural light into the mill, extending the hours it could operate. Monitor: A raised center roof section provided additional light and ventilation. Stone Foundation: Stone foundations enabled the mill to withstand floods and the constant vibration of the mill machinery. Turbines: Beginning in 1830, horizontal turbines began to replace vertical waterwheels. Turbines could produce more power with a lower volume of water. Turbines were completely under water, allowing them to operate even when the mill pond surface was frozen. The arrival of the railroad signaled the end of reliance on river transport to get flour to urban markets. Rail spurs were often built adjacent to a mill for easy loading. In only a few decades, the frontier landscape of subsistence farms became a complex of agricultural business, and technology. Many of today’s idiomatic expressions were used in the milling industry. Some examples: 1. “a millstone around my neck” meaning an onerous burden. 2. “rule of thumb” derived from the miller testing the flour between his thumb and fingers. 3. “Show us your mettle.” meaning a person’s worth in skill and ability. This derived from the stone dresser’s need to “rough” the surfaces of millstones when they wore smooth. Stone fragments, or mettle, would become embedded under his skin. By showing his mettle, the dresser could prove that he had a lot of experience. While the milling of grain is an ancient process, the nineteenth century was a turning point in surplus grain production and mechanization of the milling process. This surplus led to improved roads and waterways for grain and flour distribution to distant markets. Sources: National Register of Historic Places Documentation From “Grain Mills of Indiana, Grain Milling in Indiana 1730-1940” Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Interpretive Guide to Mansfield Roller Mill. Mansfield Roller Mill Interpretive Plan, 2004, L. Schools  This scale model of Fitch's boat, Perseverance, is in the Berlin Museum of Technology, Germany. Note that machinery and superstructure leave little room for cargo. This made Fitch's boat impractical for general use. This scale model of Fitch's boat, Perseverance, is in the Berlin Museum of Technology, Germany. Note that machinery and superstructure leave little room for cargo. This made Fitch's boat impractical for general use. Roger McCoy In the early years of the nineteenth century the increasing demands for transport of cargo, and movement of people turned many inventors’ attention to the practical use of steam power for river navigation. Their goal was to achieve speedier means of transportation. A few efforts to invent a steamboat in the eighteenth century proved to be more experimental than practical. One such effort was that of John Fitch who built a 45-foot boat that steamed up the Delaware River in 1787. His boats utilized ranks of paddles that worked in unison on both sides of the boat similar to a big canoe. Fitch’s boat was operational mechanically, but was so expensive to build that he failed to interest investors who saw little chance for adequate return. Fitch failed to pay sufficient attention to construction and operating costs and was unable to justify the economic benefits of steam navigation. He soon had to abandon his project. James Rumsey also designed a functional steam-powered riverboat in 1787, the same year as Fitch, and twenty years before Fulton. Unfortunately, Rumsey died before he had raised enough money to build the boat. Clearly the time for riverboats had arrived by the end of the eighteenth century. Robert Fulton (1765-1815) built his first boat after Fitch's death, and it was Fulton who became known as the inventor of the steam-powered riverboat. This boat, the Clermont, was both reliable and practical. Thus, Robert Fulton was the first to achieve success by building a practical steam-powered riverboat suitable for carrying both cargo and passengers. Fulton was born on a farm in Pennsylvania in 1765. When a very young man, he moved to Philadelphia where he painted portraits and landscapes. He did well, was able to send money to his mother, and eventually bought a farm near Pittsburgh where he lived with his family and his mother. At the age of twenty-three, Fulton traveled to Europe, where he lived for the next twenty years. He went to England in 1786, carrying letters of introduction from prominent Philadelphians. He had already corresponded with American artist Benjamin West, a close friend of Fulton’s father. West was the chief historical painter under the patronage of King George III. West took Fulton into his home, where Fulton lived for several years and studied painting. He gained many commissions painting portraits and landscapes, which allowed him to support himself. At the same time he continued to experiment with mechanical inventions. While in England Fulton also noticed the active canal system that carried all kinds of cargo throughout the country, and he became caught up in the English enthusiasm for canals. At that time the British canal boats were towed by horses or mules, and Fulton saw the potential for using the steam engine which had been invented by James Watt a few years earlier. His interest in art soon gave way to an interest in improving canal navigation. When he returned to America, Fulton focussed his interest in canal transportation on creating a boat suitable for river transportation. For this ground-breaking effort he became famous. In 1803, only four years before Fulton built his new boat, a Frenchman built a steam-powered river boat which broke in two and sank from the weight of the engine and machinery. Fulton went to Paris to help raise the sunken boat and study its flaws. On returning to America Fulton received money from a rich benefactor, Robert Livingston, and proceeded to design and build a boat that could bear the weight of the machinery and also carry cargo. He called his new boat the Clermont after the name of Livingston’s home on the Hudson River. The Clermont measured 130 feet long and eighteen feet wide. It had a mast and sail for addition push during good wind conditions. On each side of the Clermont, fully exposed paddle wheels fifteen feet in diameter propelled the boat through the water. One morning in August, 1807, a throng of expectant people gathered on the banks of the Hudson River at New York, to see the trial of the Clermont. Most people thought Fulton’s idea was unworkable and they expected failure. People had all along spoken of Fulton as a crackpot dreamer, and had called the Clermont "Fulton's Folly.” One quote at the time was, “Any man with common-sense knows it won’t work.” So while Fulton was waiting to give the signal to start, the crowd was making wisecracks and poking fun at his certain failure. Finally at the signal, the Clermont moved slowly, and then stood perfectly still. Skeptics jeered his failure and made “I told you so” remarks. But they spoke too soon, for after a little adjustment of the machinery, the Clermont steamed proudly up the Hudson River. As the boat continued her journey crowds of people stood along the river watching the strange sight. Some reports say that when other boatmen on the Hudson, heard the clanking machinery and saw the great sparks of fire and the volumes of dense, black smoke rising out of the funnel, they thought an evil thing had happened. One man told his wife that he had seen the devil coming up the river on a raft. The Clermont traveled 150 miles from New York to Albany in thirty-two hours. Success had at last rewarded Robert Fulton for his strong common-sense and determination. The Clermont was the first steamboat of real practical use ever invented. From that time men soon saw the immeasurable advantage of steam navigation for commercial transport on lakes and rivers. The Clermont was Fulton's last work. Fulton died in 1815 in New York City from tuberculosis, then called consumption. He had been walking home on the frozen Hudson River when one of his friends, fell through the ice. In rescuing his friend, Fulton got soaked with icy water. He is believed to have contracted pneumonia. When he got home, his sickness worsened. He was diagnosed with consumption and died at 49 years old, eight years after rendering an untold service to the industrial welfare of his country. Roger McCoy

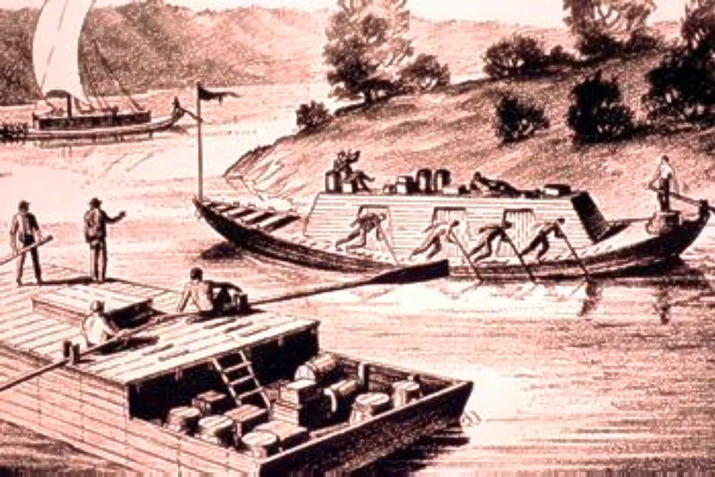

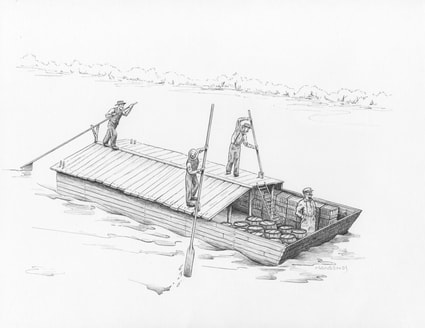

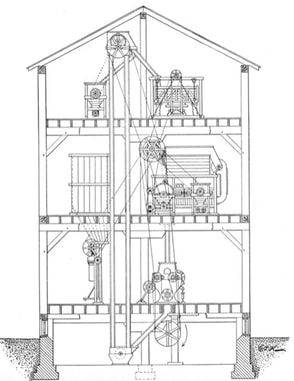

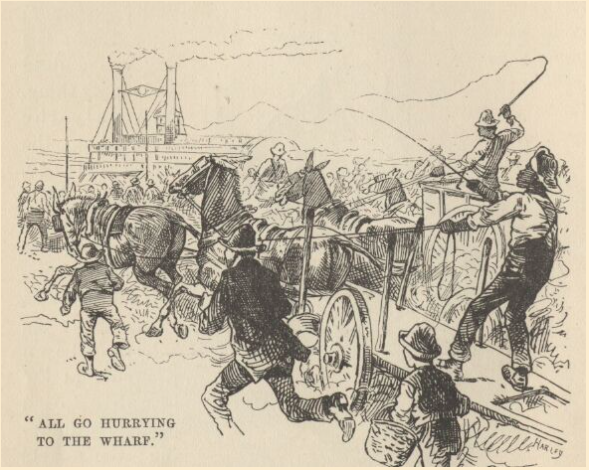

THE ENGINE ROOM The nineteenth-century riverboats were works of art as well as being the workhorse of the Mississippi River system. We’ve seen many pictures of riverboats without having much detailed knowledge about them. It would be appropriate at this time to see how the boats were constructed and operated. These boats were made primarily of wood with some iron reinforcements in the hulls of the larger boats. The length varied greatly from as short as forty feet to some monsters nearly 300 feet long. Their width ranged from ten feet to as much as eighty feet. Even such a large boat had a very shallow draft allowing them to travel in very shallow water of one to five feet deep even when loaded. This meant that even the larger boats could still dock with the bow pointing into the river bank if necessary and lower a gangplank to shore for loading people and cargo. It was commonly said that they could "navigate on a heavy dew." The overall design of the bigger boats included an internal structure of iron trusses below the main deck to prevent the long hulls from sagging. Above this structure additional decks provided cabins and passenger areas. Everything except the iron trusses was constructed from wood…stairs, galleys, and parlors. Many riverboats carried cargo with only limited room for passengers, but others focussed on passengers and became quite ornate with expensive wood trim, velvet, plush chairs, gilt edging, and other trimmings, depending on the owner's taste and budget. The construction of the engine room usually placed wood-burning boilers midship to distribute weight more evenly. To the rear of the boiler was the piston engine, also called a reciprocating engine. The piston engine had a cylinder with one steam jet pushing the piston down and another steam jet pushing the cylinder back up again with a flywheel to help maintain a smooth motion. Where does steam get its energy to push pistons up and down? Would heated air also do the job? The short answer is that any gas expands when heated, but water vapor at a boiling temperature (steam) expands six times as much as air heated to the same temperature. When the steam is in a confined spaced and not allowed to expand then the pressure is increased, and the pressure of the confined steam is six times greater than air in the same conditions. Thus when steam is confined in the boiler then injected into the cylinder the high pressure steam will push the piston. When the piston moves the volume is increased and the steam’s energy is spent and released into the atmosphere through a vent. An Englishman named Robert Boyle worked out the relationship of temperature and volume of gasses in the in the seventeenth century. Thomas Savery is credited with inventing the first practical steam engine In 1698. Miners used his engine to drive pumps to remove ground water that seeped into mines. The steamboat engines could be either at midship (for side-wheelers) or at the stern (stern-wheelers). Two rudders were added to steer the ship. These boats had surprisingly short periods of operation due to hazards such as hull damage by snags and hidden sand bars, poor maintenance, fires, general wear and tear, or the explosion of a boiler. It is estimated that an average time of operation was only five years. In the early days of riverboats, trips up the Mississippi River from New Orleans took three weeks to St Louis. Later, with better pilots, more powerful engines and boilers, and experienced boatmen who knew the location of sandbars, that figure was greatly reduced. Collisions, snags, and explosions, however, remained constant dangers. A few men who worked the steamboats took the time to write about their experience, which has provided great insight for us today. Most people know of Mark Twain and his experience as a riverboat pilot. Another man, George Merrick, also wrote about his life on a riverboat in every capacity from the hard labor in the engine room to eventually becoming a riverboat pilot himself. Although not so eloquent and entertaining as Twain, Merrick actually gives more detail about the interior operations and the functions of each crew member on the boat. He writes that the vital core of the riverboat was the engine room and the engineer responsible for its operation. Like many career boatmen Merrick started as a “cub” (trainee) in the engine room. Work in the engine-room had the worst working conditions on the boat with heat and steam from the boiler filling the room. Merrick writes that: A drawback in the life of a cub engineer was the fact that when in port there was no let-up of work. In fact the worst part came then. In port the pilots were at liberty until the hour of sailing; not so with the engineers. As soon as the fires were drawn, the water let out of the boilers, the process of cleaning began. Being a slim lad one of my duties is to creep into the boilers through the manhole. With a hammer and a sharp-linked chain I must “scale” the boilers by pounding on the two large flues with the hammer, and dragging the saw-chain around until all the accumulated mud and sediment is loosened. [ NOTE: The sediment accumulated from silt in the river water that was drawn to fill the boilers.] Merrick describes in great detail the work of the various crewmen working in the engine room. He explained that the boats had two engineers. The first engineer had many years of experience and was responsible for the proper maintenance and operation of the machinery. The second engineer did much of the work maintaining the engines, and keeping the boilers supplied with enough water to prevent overheating and possible explosions. Several assistants or trainees might also work in the engine room. After a stint in this difficult and dirty job Merrick asked about a different job away from the engine room. Apparently he had done a suitable job in the engine room as his request was granted and he replaced the second office clerk who recently had a disabling injury. Everything changed for the better when Merrick became second clerk, called the “mud clerk.” “As second clerk all these conditions were changed. In the absence of the chief clerk, his assistant took charge of the office, answered all questions of passengers, issued tickets for passage and staterooms, showed people about the boat, and in a hundred ways made himself agreeable, and so far as possible ministered to their comfort and happiness while on board. The reputation of a passenger boat depended greatly upon the esteem in which the captain, clerks, and pilots were held by the traveling public. The fame of such a crew was passed along from one tourist to another, until the gentle accomplishments of a boat's personnel were as well known as their official qualifications.” Merrick eventually worked up through the ranks to the much coveted job of pilot. In the process of following his career we learn much about the operation of the iconic riverboats of the Mississippi River. Sources: Merrick, George. Old Times on the Upper Mississippi: The Recollections of a Steamboat Pilot from 1854 to 1863. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur Clark, Company. 1909. Old Times on the Upper Mississippi: The Recollections of a Steamboat Pilot from 1854 to 1863. Retrieved from: gutenberg.org/cache/epub/47262/pg47262-images. Retrieved from: wikipedia.org/wiki/Steamboats of the Mississippi: Construction of the vessels.  Flatboat and keel boat on the Ohio River in late 18th century. Artist unknown. Public Domain Flatboat and keel boat on the Ohio River in late 18th century. Artist unknown. Public Domain Throughout most of the nineteenth century, steamboats plied the Mississippi River day and night, stopping at many little towns along the shores. For those towns the regular visit of the riverboat was their lifeblood, providing all the necessities for daily life. The local merchants received their supply of merchandise via the riverboat’s regular visits. The local hardware, clothing, and food outlet was all under the roof of the General Store and everyone in town had an interest in seeing the new goods coming in from far-off places. Mark Twain was a keen observer of life in small towns along the river and wrote vivid accounts of the daily arrival of the steamboat. His description of the excitement among all the people when a big boat arrives in a small town gives a clear picture of the importance of the riverboats. Once a day a cheap, gaudy packet (riverboat) arrived upward from St. Louis and another downward from Keokuk (Iowa). After all these years I can picture that old time just as it was then. The town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer’s morning, the streets nearly empty, one or two clerks sitting in front of the Water Street stores with their splint-bottomed chairs tilted back against the wall, chins on breasts, hats slouched over their faces, asleep. A sow and a litter of pigs loafing along the sidewalk doing a good business in watermelon rinds; two or three lonely little freight piles scattered about the levee. Nobody listened to the peaceful lapping of the wavelets against the wharf while the great Mississippi, the majestic, the magnificent Mississippi rolled its mile wide tide along. Presently a film of dark smoke appears coming around the bend. Instantly a drayman lifts up the cry, “STEAMBOAT A-COMIN” and the scene changes! The town comes to life, The clerks wake up, a furious clatter of drays follows, people pour from every house and store. All in a twinkling the dead town is alive and moving. Drays, carts, men, boys all go hurrying to the wharf. Assembled there the people fasten their eyes on the coming boat as though a wonder they are seeing for the first time. Twain’s graphic description of the steamboat coming to town shows the importance of the rivers with steamboat traffic in the daily lives of people living in the many small villages in rural areas of the country. The river’s earliest boat traffic, however, was big barges—keelboats and flatboats that had to be poled or warped when traveling upstream. Warping is a means of moving against the current by throwing an anchor ahead of the boat then pulling the boat by hand toward the anchor. Then repeat, repeat, and repeat. The bargemen floated and sailed from the upper states down to New Orleans. There they changed cargos and tediously warped and poled by hand all the way to upper-river ports. A single round trip from St. Louis sometimes took nine months. The large number of barges in constant use required hordes of hardy men who endured terrific hardships. Twain describes these men as, “rough, rude, uneducated, brave, stoic, heavy drinkers, coarse frolickers who frequented the moral sties of the river-front towns. They were heavy fighters, reckless fellows, jolly, profane, extravagant with their money, and bankrupt soon after the end of their trip.” Despite these traits, Twain added that these barge-men were mainly honest, trustworthy, faithful to their duties, and usually quite generous. Abe Lincoln had a brief stint as a barge-man on his own barge. At the age of nineteen Lincoln built a flatboat and ran a load of farm produce from Kentucky down the Mississippi to New Orleans. Once there he sold the barge for its timbers and returned home. There he had to give all his earnings to his father…with considerable resentment. When Abe was twenty-one, the family moved to Illinois just west of Decatur. Following this move, Abe built a second flatboat and made another run down river, but this time as an independent operator. After that haul, he lived on his own, moving to the town of New Salem, Illinois in 1831. In 1807 a commercially practical steamboat was invented (future blog) and gradually replaced the barge. For fifteen or twenty years the flatboats continued to carry loads downstream where the boatmen would sell their loads and their boats, but the upstream trip was taken over by steamboats. The boatmen would return home as deck passengers on the steamboats. Mark Twain had some further comment on the big barges plying the Mississippi: …the river from end to end was flaked with coal-fleets and timber rafts, all managed by hand, and employing hosts of the rough characters whom I have been trying to describe. I remember the annual processions of mighty rafts that used to glide by Hannibal when I was a boy,—an acre or so of white, sweet-smelling boards in each raft, a crew of two dozen men or more, three or four wigwams scattered about the raft's vast level space for storm-quarters,—and I remember the rude ways and the tremendous talk of their big crews, for we used to swim out a quarter or third of a mile and get on these rafts and have a ride. It was his many recollections of river life that guided Twain’s account of Huck Finn rafting down the river. Twain describes his own boyhood in Life on the Mississippi, stating that "there was but one permanent ambition" among his comrades: to be a steamboatman. He wrote, "Pilot was the grandest position of all.” Eventually Twain was taken on as a cub (trainee) pilot for $500 per year (equivalent to $17,800 in 2022). A later blog will describe the role of pilot and other crewmen on the riverboats. Sources: Twain, Mark, Life on the Mississippi, Boston James Osgood and Company, 1883. (Released as EBook 2006) Retrieved from Project Gutenberg Mark Twain: Early Life. Retrieved from wikipedia.  Typical river boat of the nineteenth century. Note barrels and bales of goods waiting to be loaded. Artist, Michael H. Yeager Typical river boat of the nineteenth century. Note barrels and bales of goods waiting to be loaded. Artist, Michael H. Yeager Roger M. McCoy Water routes soon became as important as wagon trails for migration and the movement of goods in the nineteenth century. With the increased use of waterways also came a proliferation of river boats of many designs and purposes. This series of blogs explores the development and use of river boats on the inland waterways: types of boats, men who invented them, first person accounts of men who stoked the fires, handled the loads, and piloted the boats, along with all the hazards of river travel and some of the notable ship wrecks. First, let’s look at the fortunate geography of rivers in the United States and how they became major routes for developing the land. The Mississippi River provides an extensive waterway that stretches from the southernmost to the northernmost extremities of the United States from the Gulf of Mexico in the south and pointing toward Canada at the north end. From the east the Ohio River, with its tributaries stretching to the Allegheny range in the central Appalachians, flows into the Mississippi. The largest of the Ohio River tributaries, the Tennessee River, drains most of Tennessee plus part of northern Alabama, Georgia, and western Virginia. From the west the Missouri and Arkansas Rivers flow eastward out of the Rocky Mountains joining the Mississippi. The total area drained by the Mississippi River system covers forty-percent of the 48 contiguous states, much of which is agricultural or rangeland. This immense river basin was viewed very early as a vital corridor for an expanding empire, and for a century the three great rivers (Mississippi, Ohio, and Missouri Rivers) served as major routes for movement into the new land that became the United States. President Thomas Jefferson was among those who saw the potential of the vast land and sent Lewis and Clark on an expedition in 1804 to explore and map the region. John Frémont, John Powell, Edward Steptoe, and others continued the great western mapping project. With the addition in 1825 of the Erie Canal from Lake Erie to the Hudson River, it became possible to travel by boat from New York to Lake Michigan. Later a 96 mile-long Illinois and Michigan Canal was built from Lake Michigan to the Illinois River. When that was completed in 1848 it was possible to transport goods by river and canal from New York City to the Gulf of Mexico and all points between without using a seagoing vessel and avoiding the hazards of sea travel. The young nation was now connected from its northern border to the Gulf Coast and eastward to New York. Explorers and trappers traveled westward via the Missouri River to the Northern Rockies very early, but the Missouri was considered a more dangerous route for larger boats because of its strong currents, snags, and sandbars. From the beginning of U.S. history the Mississippi was seen as the single most important river on the American continent. Its 1,245,000 square-mile drainage basin covers most of the central plains of the United States from the Appalachians to the Rockies. It became an essential waterway considered vital to the ambitions of an expanding nation and the key to what many called “Manifest Destiny.” Manifest Destiny, a phrase coined in 1845, espoused the idea that the United States was destined by God to expand its dominion and spread democracy and capitalism across the entire North American continent. It became a rallying cry in the mid-nineteenth century for westward expansion and the river routes in the mid-continent were an essential component of that expansion. People and goods could travel on rivers and canals from New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Tennessee to the Gulf of Mexico or west into the northern Rocky Mountains, including present day Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. In the beginning the only means of river travel was on rafts, flatboats, or keel boats, but they required poling or rowing and moved very slowly, especially when moving upstream. Many men earned money poling cargo rafts down the Mississippi, including young Abraham Lincoln of Illinois. Fortunately that difficult mode of travel was soon to change. A first effort at steam-powered boats was made in 1787 by American John Finch who constructed a boat with eight steam-powered oars on each side. Finch’s steamboat never progressed beyond the experimental stage before it was superseded by a more practical steamboat designed by Robert Fulton. A New York City inventor and engineer, Robert Fulton became interested in steam power while visiting England, where he saw the steam engine invented by James Watt in 1776. After seeing the Watt engine, Fulton returned to the U.S. and in 1807 applied a steam engine of similar design to a boat, the Clermont, creating the world’s first commercially successful steamboat with a paddle wheel. Although Fulton’s steamboat first traveled only the Hudson River Valley, the potential for steamboats on the great interior river system became immediately apparent. Since that time the Mississippi and its tributaries have become important routes for cargo to and from Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Omaha, Nebraska, Minneapolis, MInnesota, down to New Orleans and all points between. Canals connect the Great Lakes into the system via the Illinois River and eastward to New York via the Hudson River or along the St Lawrence River to the Atlantic. |

Archives

April 2023

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed