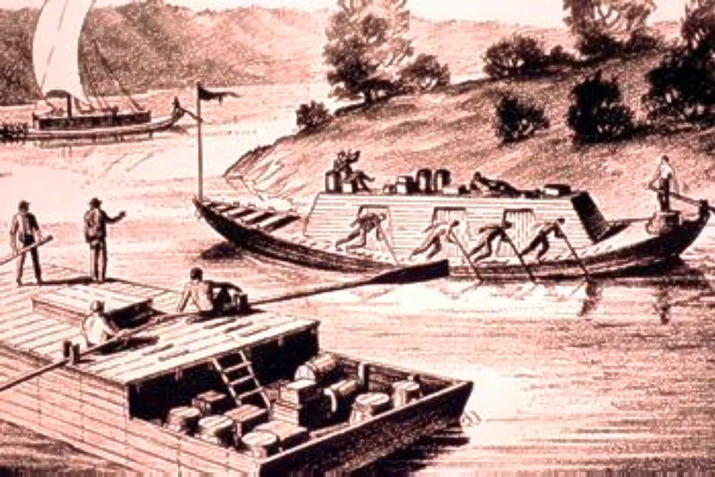

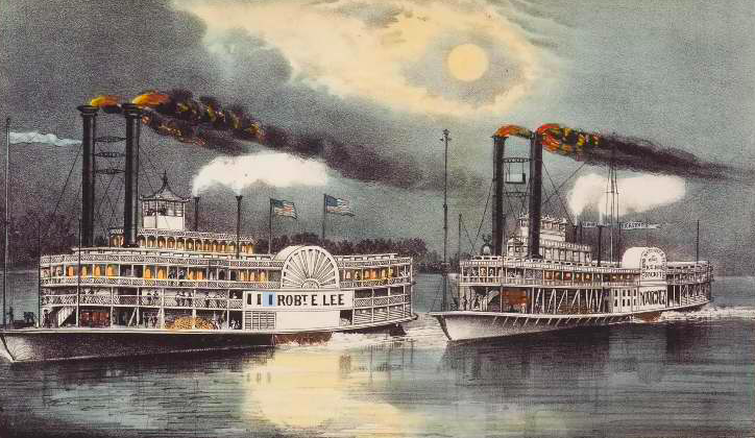

Flatboat and keel boat on the Ohio River in late 18th century. Artist unknown. Public Domain Flatboat and keel boat on the Ohio River in late 18th century. Artist unknown. Public Domain Throughout most of the nineteenth century, steamboats plied the Mississippi River day and night, stopping at many little towns along the shores. For those towns the regular visit of the riverboat was their lifeblood, providing all the necessities for daily life. The local merchants received their supply of merchandise via the riverboat’s regular visits. The local hardware, clothing, and food outlet was all under the roof of the General Store and everyone in town had an interest in seeing the new goods coming in from far-off places. Mark Twain was a keen observer of life in small towns along the river and wrote vivid accounts of the daily arrival of the steamboat. His description of the excitement among all the people when a big boat arrives in a small town gives a clear picture of the importance of the riverboats. Once a day a cheap, gaudy packet (riverboat) arrived upward from St. Louis and another downward from Keokuk (Iowa). After all these years I can picture that old time just as it was then. The town drowsing in the sunshine of a summer’s morning, the streets nearly empty, one or two clerks sitting in front of the Water Street stores with their splint-bottomed chairs tilted back against the wall, chins on breasts, hats slouched over their faces, asleep. A sow and a litter of pigs loafing along the sidewalk doing a good business in watermelon rinds; two or three lonely little freight piles scattered about the levee. Nobody listened to the peaceful lapping of the wavelets against the wharf while the great Mississippi, the majestic, the magnificent Mississippi rolled its mile wide tide along. Presently a film of dark smoke appears coming around the bend. Instantly a drayman lifts up the cry, “STEAMBOAT A-COMIN” and the scene changes! The town comes to life, The clerks wake up, a furious clatter of drays follows, people pour from every house and store. All in a twinkling the dead town is alive and moving. Drays, carts, men, boys all go hurrying to the wharf. Assembled there the people fasten their eyes on the coming boat as though a wonder they are seeing for the first time. Twain’s graphic description of the steamboat coming to town shows the importance of the rivers with steamboat traffic in the daily lives of people living in the many small villages in rural areas of the country. The river’s earliest boat traffic, however, was big barges—keelboats and flatboats that had to be poled or warped when traveling upstream. Warping is a means of moving against the current by throwing an anchor ahead of the boat then pulling the boat by hand toward the anchor. Then repeat, repeat, and repeat. The bargemen floated and sailed from the upper states down to New Orleans. There they changed cargos and tediously warped and poled by hand all the way to upper-river ports. A single round trip from St. Louis sometimes took nine months. The large number of barges in constant use required hordes of hardy men who endured terrific hardships. Twain describes these men as, “rough, rude, uneducated, brave, stoic, heavy drinkers, coarse frolickers who frequented the moral sties of the river-front towns. They were heavy fighters, reckless fellows, jolly, profane, extravagant with their money, and bankrupt soon after the end of their trip.” Despite these traits, Twain added that these barge-men were mainly honest, trustworthy, faithful to their duties, and usually quite generous. Abe Lincoln had a brief stint as a barge-man on his own barge. At the age of nineteen Lincoln built a flatboat and ran a load of farm produce from Kentucky down the Mississippi to New Orleans. Once there he sold the barge for its timbers and returned home. There he had to give all his earnings to his father…with considerable resentment. When Abe was twenty-one, the family moved to Illinois just west of Decatur. Following this move, Abe built a second flatboat and made another run down river, but this time as an independent operator. After that haul, he lived on his own, moving to the town of New Salem, Illinois in 1831. In 1807 a commercially practical steamboat was invented (future blog) and gradually replaced the barge. For fifteen or twenty years the flatboats continued to carry loads downstream where the boatmen would sell their loads and their boats, but the upstream trip was taken over by steamboats. The boatmen would return home as deck passengers on the steamboats. Mark Twain had some further comment on the big barges plying the Mississippi: …the river from end to end was flaked with coal-fleets and timber rafts, all managed by hand, and employing hosts of the rough characters whom I have been trying to describe. I remember the annual processions of mighty rafts that used to glide by Hannibal when I was a boy,—an acre or so of white, sweet-smelling boards in each raft, a crew of two dozen men or more, three or four wigwams scattered about the raft's vast level space for storm-quarters,—and I remember the rude ways and the tremendous talk of their big crews, for we used to swim out a quarter or third of a mile and get on these rafts and have a ride. It was his many recollections of river life that guided Twain’s account of Huck Finn rafting down the river. Twain describes his own boyhood in Life on the Mississippi, stating that "there was but one permanent ambition" among his comrades: to be a steamboatman. He wrote, "Pilot was the grandest position of all.” Eventually Twain was taken on as a cub (trainee) pilot for $500 per year (equivalent to $17,800 in 2022). A later blog will describe the role of pilot and other crewmen on the riverboats. Sources: Twain, Mark, Life on the Mississippi, Boston James Osgood and Company, 1883. (Released as EBook 2006) Retrieved from Project Gutenberg Mark Twain: Early Life. Retrieved from wikipedia.

2 Comments

Dennis Fitzsimons

8/8/2022 04:04:02 pm

Looks like more interesting adventures ahead!!

Reply

Roger McCoy

8/9/2022 02:53:07 pm

Let's hope so. Stay tuned.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

April 2023

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed